The events of spring 1861 are well known. Civil War has begun, political and social discord have given way to the full blown secession of seven southern states. Armies are forming and bullets are beginning to fly. Now imagine this: you are one of the VERY first volunteers in the entire country to answer the President’s call for troops. Within hours of leaving home, you are moved straight to the front with no training, no equipment, and no uniform. After ninety days of suffering through lack of supplies, mistreatment, friendly fire, skirmishing with the enemy, and even murder and suicide from within, you now prepare to head home. The commanding general requested you to stay another two weeks, but as your regiment can’t come to a consensus, you start homeward. Coincidentally the next day, the two largest forces to meet on the battlefield thus far wage a bitter fight, which results in a disastrous defeat for the Federal army. The prospects of a quick resolution to the conflict have been left in the ashes, and to your disbelief, the General has named YOU and your comrades personally responsible for the defeat…and you weren’t even there.

This is exactly what happened to the men who served in the Fourth Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, a ninety days regiment raised largely out of Norristown / Montgomery County in southeastern Pennsylvania. They enlisted on April 20, 1861, which meant their enlistments were up on July 20th, 1861; the day before the battle of First Manassas. The regiment left the field to return home, their terms of service met and honorably discharged by the commanding General. They were not aware that a battle was to come; by all accounts, they believed nothing of any note was to come any time soon; that changed when battle broke out after they had left the field. The Fourth did not keep going, and even assisted in covering the retreating army as they streamed towards Washington. Despite their efforts, despite ninety days of exemplary service, General Irvin McDowell would point out this regiment BY NAME in his after action report as one of the key factors of the defeat.

This article will focus on the details of their experiences during their 90-day enlistment. By doing so, we hope to better understand the motives of these men, who, on that hot July afternoon, decided to go home instead of heed their general’s request. This is the story of how this group of Montgomery County patriots, some of the very first to answer their President’s call, became the scapegoats of the first great battle of the Civil War.

Mr. Lincoln’s Call

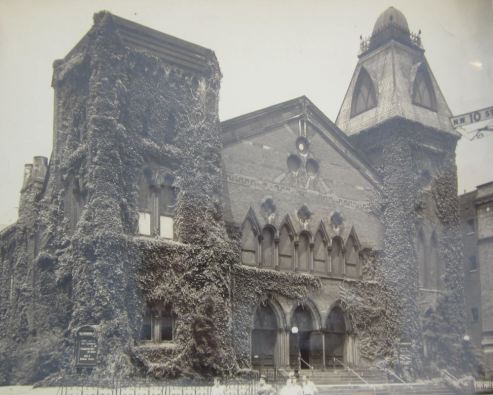

The 16th of April, 1861, found a large patriotic gathering at the Montgomery County Courthouse in Norristown, Pennsylvania. Following the bombardment at Ft. Sumter in Charleston Harbor a few days earlier, patriotic fervor ran through the streets of many cities in America, and Norristown was no exception. Word had come the previous day of President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 men to serve 3 months, and the citizenry responded in true patriotic form. A meeting was called that night at the Odd Fellows Hall on Main Street, and the local militia company, commanded by 30 year old John Frederick Hartranft, offered up it’s services. The idea was that this group would become the nucleus of a regiment raised with only men from Montgomery County.

A modern view of the Norristown Odd Fellows Hall, where the meeting was held to discuss the raising of what became the Fourth PVI.

The following day, April 17th, the men officially offered up their service for 90 days to Governor Curtin. Recruiting began immediately, and within three days the once small militia company had swelled its ranks to 7 full companies of 75 men each; the ranks of company “A” would even reach 115 men. By the morning of April 20th, the new regiment prepared to leave for the state capital with nearly 600 men. All business in the city was suspended, and the population of town came out in droves to see the brave men go off to war. In front of the Courthouse, Judge Daniel M. Snyder presented the men with a stand of colors from the women of Norristown, in front of a “dense and weeping assembly.”

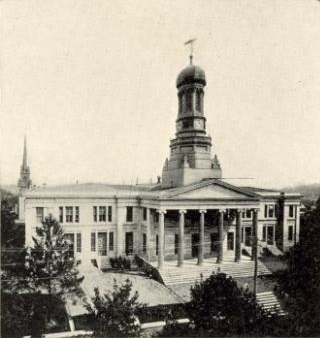

19th Century view of Montgomery County Courthouse, where the Fourth was presented its’ colors on April 20, 1861.

The regiment left by train, and arrived in Harrisburg about 2 p.m. on Saturday, April 20th. The original goal was to remain at Harrisburg until the ranks could be totally filled to quota with recruits from Montgomery County. However, the Federal government decided the urgent need to move towards the seat of war was more paramount. Men from Delaware, Union, and Centre counties would make up the last three companies instead, though that didn’t stop the local Norristown newspapers from still referring to the unit as “The Montgomery County Regiment.” It was here during this brief time at Camp Curtin that the regiment received it’s official designation as the “Fourth Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.”

Elections were held before the regiment left camp, and the same officers that had existed in the militia regiment maintained their ranks in the new organization. The highest staff positions were all filled with men from Norristown :

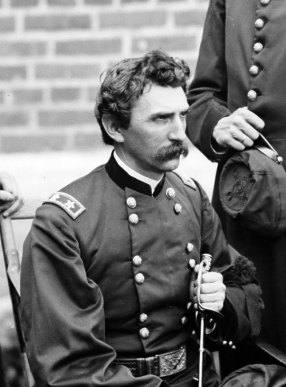

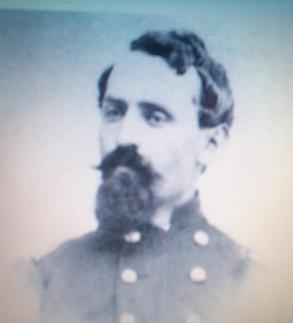

John F. Hartranft, Colonel

Edwin Schall, Major

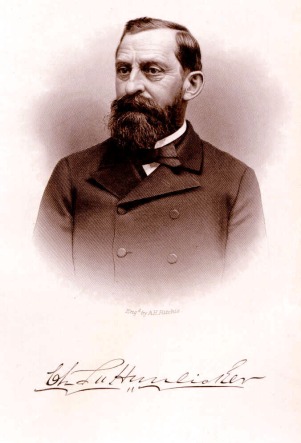

Charles Hunsicker, Adjutant

(Edward Schall was elected Lieutenant Colonel, however there is no known photograph of him.)

Moving to the Front

The Fourth was only in Harrisburg for approximately 30 hours before it received it’s marching orders to leave for the front. They left by train at 7 pm, no uniforms on their backs other than what some of the men who had previously served in the militia still owned. No accouterments or tentage had been issued; the men only had coarse white blankets slung over their shoulders, and hard crackers in their pockets. They reached Philadelphia around 12 midnight and slept right on the train platform until roused at about 4:30 a.m. Here they were issued old converted Harper’s Ferry flintlocks, which replaced “Minie Rifled Muskets” that they had originally left Norristown with; according to the journal of Captain William Bolton of Co. “A,” the government did not even possess proper ammunition for them. They were placed back on railroad cars, and were sent on their way to Perryville, Maryland. Once arrived, the Fourth was placed under the direct command of Col. Charles P. Dare, commander of the Twenty-Third Pennsylvania, another ninety days regiment that had been organized in Philadelphia.

Colonel Dare took one company of the Twenty-Third, and the entire Fourth Pennsylvania, to Perryville to take hold of the town. The primary goal was to keep it out of Confederate hands, and position the troops in such a fashion that it would deter and prevent any kind of surprise attack. The regiment would remain in this position for only a few days, but they would be eventful in the most unfortunate of ways.

The Flag of the Fourth PVI, presented to them at the Montgomery County Court House, April 20, 1861. This flag would later be the 1st national flag of the Fifty-First PVI, until just after the battle of Antietam.

The First Casualties

The first casualty of the Fourth would not come at the hands of a Confederate soldier, and it wouldn’t even be caused by disease; it would come at the hands of another Federal soldier. Three days after leaving Norristown, the Fourth had their sentinels placed out on picket near Perryville. A group approached the post of 41 year old Private William Rapine of Co. “B.” in the darkness, approximately 2 a.m. The soldier had orders to not let any man pass without the countersign, so per his duty, Private Rapine challenged the group. An officer stepped forward and responded, but the sentinel did not receive the proper response. Rapine challenged again, but again did not receive what he believed was the proper response. The officer declared who he was, that he was Colonel Charles Dare of the Twenty-Third Pennsylvania, and his commanding officer. He demanded to be let by with his group immediately. The green private denied that he was in fact who he said he was; with that Rapine fired a warning shot.

The reports on what happen next differ depending on where you read the account. In the local newspaper, The Norristown Free Press and Herald, Colonel Dare tripped and fell, and his group hit the ground to avoid the shot. At that point Private Rapine rushed at the Colonel with his bayonet, and to save his own life, Dare ordered another sentintel to fire on Pvt. Rapine. Knowing how quickly this incident happened, in a matter of seconds, and the distance that is usually between soldiers on post, the plausibility of this scenario is highly unlikely.

The account of Captain Bolton, who, unlike the newspaper writers back home, was actually in the vicinity of the incident, and states the situation a bit differently:

“April 22…Private Wm. Rapine of Company B was shot and killed on the spot by Col. Dare under very sad circumstances. We all hold that Dare was not justifiable in doing what he did. Rapine was a sentinel, and on duty, with orders. This officer attempted to pass. Rapine challenged him. The challenge was unheeded. Rapine fired, which he had a right to do so. Dare returned the fire and killed Rapine on the spot. Wm. S. Rapine was a good soldier, and was only doing his duty as a sentinel when we was shot down. Had he lived, he would have made his mark in the service.”

Regardless of who fired the bullet, it killed Rapine on the spot; and whether he pulled the trigger or simply gave the fateful order, the murderer was none other than Colonel Charles Dare himself. The men in the Fourth agreed that this death was unjustifiable and that the Colonel was grievously in the wrong. They mourned their friend, who was considered to have a “kind demeanor” and was a well known musician back home in the Norristown Cornet Band. William would also leave behind a wife and 8 children, ranging from 3 to 19.

Article from the Norristown Free Press & Herald, April 30, 1861, describing the death of Pvt. William Rapine.

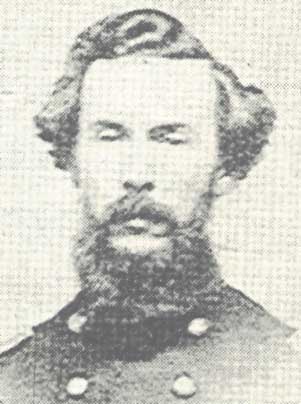

Despite the injustice, Colonel Charles Dare retained his command and never faced charges. He would leave the service on his own shortly after the 90 day enlistment of the Twenty-Third Pennsylvania came to an end. He would pass command to a man who would make the regiment well known, Colonel David Birney, who would lend his name to their famous designation, “Birney’s Zouaves.” Charles Dare himself would die of disease just two years later, in the fall of 1863, and is buried in beautiful Laurel Hill Cemetery, just outside of Philadelphia. William Rapine’s body was sent home and buried in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery of Norristown, once on a lovely hill top overlooking the city. Today, that cemetery is under a parking lot.

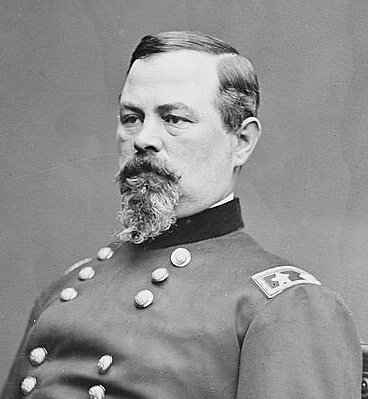

Colonel Charles P. Dare, Twenty-Third PVI, the man who shot and killed Pvt. William Rapine of Co. “B.”

The following day, the second casualty occurred, and could be considered even more tragic than the first. After several days of constant travel, drilling, little sleep, and even less food, one private decided he could take no more. Perhaps the news of the unjust death of William Rapine was what pushed him over the edge. Whatever the case, Corporal William Biggs of Co. “E,” left camp without permission, wandered down along the Potomac to an “out-of-away place” and shot himself.

According to Captain Bolton’s journal, Biggs’ body was sent back to Norristown along with that of William Rapine. On May 3, his family laid him to rest in Franklin Cemetery in Philadelphia. In the 20th Century, urban development would cause the city of Philadelphia to move Franklin Cemetery and all of it’s interments, but financial scandal would rock the entire effort. Today, those bodies lie in unmarked mass graves in the vicinity of Bensalem, Pennsylvania; Corporal Biggs’ remains among them. Interestingly, William Biggs’ is listed on the official muster roll of the regiment as having been mustered out of July 21, 1861 with the rest of the organization; not entirely sure if this is simply a clerical error, or if the unsettling manner of death compelled the regimental clerks to leave this fact out of official documentation.

Whatever the case, life in camp would begrudgingly continue despite these tragedies.

Onward towards Washington

After only a few days in the area of Perryville, Colonel Dare received orders to move his command immediately towards Washington. Transportation was secured via the steamship Annapolis, as recent attacks on Federal soldiers in Baltimore made it unsafe to pass through via train. Dare split the Fourth into two wings; the left-wing, Companies B, E, G,H, and I, under the command of Lt. Col. Schall, remained in Perryville to hold the town for several more days.Companies A, C, D, F, made up the right-wing of the regiment, under Colonel Hartranft, and they began the trip down the Chesapeake Bay to Annapolis, MD late on the evening of April 24th.

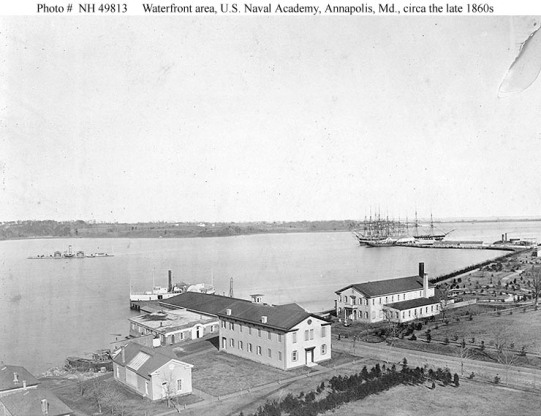

The Annapolis moved slowly down the bay as storms passed continually through the night. At some point, the lights of another ship were seen in the distance. Captain Bolton of Co. “A” noted in his journal that the commander of the steamer did not make the appropriate signal to the mystery ship…as such, the shadowy ship drew closer. The soldiers of the Fourth watched as the ship got so close that they could actually hear the commander of this vessel yelling commands. Through the darkness, these Pennsylvania soldiers realized what they were up against : the mystery vessel was none other than the most famous ship in the entire U.S. Navy; “Old Ironsides” herself, the U.S.S. Constitution…and it’s Commander, Lieutenant George Washington Rodgers II, thought the Annapolis was an enemy vessel.

The men of the Fourth could only sit in horror as the most powerful frigate in the Navy opened it’s port holes, and Lieutenant Rodgers gave the command to man and load the guns. Shouting on both ships echoed through the bay, and at the last moment, Lt. Rodgers yelled across the water to the steamer, demanding to know who it was on the mystery ship he was about to fire upon. Lt. Dunlap, the surgeon of the regiment, quickly responded “The right wing of the Fourth Pennsylvania, on their way to Annapolis!” With that, the disaster was averted, the men aboard both vessels let out a mighty cheer for the Union, and both ships went on their way.

An 1860’s photo of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, MD., where the Fourth briefly quartered in the spring of 1861. In the distance are the frigates Santee and Constitution, the latter of which nearly sank the steamer the Fourth was travelling on the night of April 24, 1861.

The men would arrive safely at about 2 a.m., and later that morning they disembarked and were quartered in the buildings of the U.S. Naval Academy itself. It was during this stretch of time that the Fourth finally received their first batch of uniforms to much rejoicing…until the packages were opened.

“Are we not finely suited?”

The men left Norristown with their own clothes on their back; they received no clothing issue when they left Harrisburg. The wait to receive proper uniforms would take longer than anyone in the regiment would ever expect; this became a great point of contention for both the men in the field, and the supportive citizens back at home.

A humorous poem about the dreadful state of the uniforms originally issued to the Fourth; printed in the Norristown Herald and Free Press, May 1861. The name “John Phoenix Jr.” does not appear on any of the rolls of the regiment.

What follows is a sampling of some of the uniform and supply issues, from the diary of William Bolton, Captain of Co. “A.”

April 21 – “We had not been provided haversacks or canteens, but were each given a blanket which was rolled up and strung over our shoulders. We were all very hungry, and the boys discovered barrels of dried beef cut into pieces of about four inches square (they declared it to be horseflesh)…we all had very sore mouths the next morning…When we left Norristown, we all carried the Minie rifle musket, a good arm, but the state had no ammunition on hand to suit that class of guns…we were given old condemned Harpers’ Ferry muskets which had once been flintlocks. “

April 28 – “Clothing arrived for us, and it is all kinds of fits.”

April 30 – “The men are all impromptu tailors altering their clothes to make them fit.”

May 5 – “Engaged all day in issuing the new uniforms, shoes, caps &c. to the company. Gray pants, blue blouses and caps. All hands looking very grotesque in their ill fitting clothes, and quite all of the men had to have their pants and blouses, also their caps altered. Fortunately, I had a a number of tailors in the company, and I put them to good work, and they did very willingly, and the men in a day or two looked more presentable.”

May 8 – “…arrived in Washington about 6 1/2 o’clock P.M. A great crowd was at the depot to meet us expecting to find a splendid equipped regiment, but they were disappointed. All our dirty clothes bundled up in our dirty white blankets (once white) strapped on our backs, as we had no knapsacks. We were indeed a sorry set of looking objects, and a great deal of fun was poked at us as we marched up Pennsylvania Avenue. There were friend and foe on the side walks, but we kept our temper, knowing that if we should be attacked, we had our guns, and plenty of ammunition, and the hearts and the courage to use them should it be required…”

May 27 – “…today I was presented with a number of haverlocks for my men, by a citizen of Washington.”

June 13 – “Received a lot of red shirts and gum blankets.”

The lack of uniforms and equipment was disheartening and hurt the pride of the regiment to a degree, but the men did their best to keep their spirits high. One soldier, only identified as “H.K.W.,” would write home to the Norristown Herald and Free Press, “…we startled several fancy men who asked us where our equipments were, by telling them we came to fight, and not make a show.”

Washington City

On May 8th, the Fourth Pennsylvania finally arrived in the nation’s capitol. Over 2 weeks into their enlistment, they had still not been provided with proper tentage or mess gear, so they could not go into camp with the rest of the army; the regiment was forced to take shelter in the assembly buildings and churches around Washington. These close quarters would lead way to disease running rampant in the ranks, and Typhoid Fever would wreak havoc. Typhoid would send several soldier’s back home to Norristown, including brothers John and Charles Styer, and it would claim the life of Orderly Sergeant David Knipe, of Co. “E.”

The First Congregational Church of Washington. Companies A and F would quarter in this building and drill in it’s churchyard during the early weeks of May, 1861.

While camped in Washington, the Fourth witnessed a spectacle that to them was beyond belief. During the first few weeks in and around Washington, the Montgomery Regiment was camped within eyesight of Elmer Ellsworth and his famous Fire Zouaves. Earlier in the month while in Annapolis, Corporal Charles Iredell of Co. “A” would note the arrival of the famed regiment in a letter to the Norristown Free Herald and Press :

May 4, 1861 : “On Thursday, Col. Elsworth’s regiment of Zouaves, from New York, eleven hundred men strong, arrived here on their route to Washington. On their disembarking, they formed on the space between the college buildings and the river, guards of their men being placed to prevent them from leaving the place allotted to them. Squads of them, however, managed to pass the guards, and they soon swarmed over the grounds like a disturbed nest of hornets. One of the proprietors of the numerous refreshment stands happening to offend them, they soon cleared the ground of the unfortunate vendors of edibles, oysters, fish, cakes and coffee being strewed over the ground in elegant confusion. After this heroic exploit, several attempted to pass the gate and proceed to the city. At one of these, our friends Heenan and Spencer of the Keystone Rifles, were stationed as sentinels, and some half a dozen Zouaves were determined to pass. To any one acquainted with the gentlemen named, it is scarcely necessary to say that they did not succeed in getting through, and the “Zoozoo’s” found conquering huckster women, and a live specimen of the Fourth regiment, an entirely different undertaking.”

On May 23rd, Virginia voted to secede from the Union. The next day, 11 regiments from the forces around Washington moved across the Potomac and quickly captured Arlington, while the First Michigan and Colonel Ellsworth and his famous Zouaves took steamers down the river to take Alexandria and clear it of any Confederates. The Fourth did not participate in these movements, and later on in the day, wild rumors began to circulate that Ellsworth had been shot and killed during the action; the rumors were dismissed by most, but many soldiers gathered at the dock as the steamer containing the New York firemen arrived, to finally find out for sure. To their horror, they watched as the lifeless body of the 24 year old Colonel was unloaded off of the steamship. Charles Iredell would once again write home to describe a much somber scene, and no doubt reflect the emotions of many of the men who were present :

May 24, 1861 – “You have heard, or will have heard before this reaches you, of the death of the gallant Col. Ellsworth. When the news first reached our camp, our indignation was subdued by the hope that the rumor would prove to be unfounded. We awaited anxiously the arrival of the steamer from Alexandria, trusting that this, as so many evil tidings had hitherto proved, might be incorrect. But that steamer brought with it his lifeless body, sacrificed in tearing from its unworthy height the emblem of treason, and flinging to the breeze the banner of liberty. Of courteous address, winning manners, and of almost unequaled courage and daring, Ellsworth was the favorite of all, the beloved of his friends, the admired of those who knew him only by his fame as a gallant commander and brave soldier. The death of the assassin seemed but slight retribution for his untimely end. ‘Twas life for life, blood for blood, but how unlike in value!”

The sadness following this event would soon pass, and tents would finally be received in late May. The men were finally able to leave the dank and sickening confines of the buildings of Washington, and move into a proper camp at Bladensburg, two miles outside of the city. Drills and inspection would begin in earnest here, and all measures were taken to help make the Fourth Pennsylvania a properly drilled fighting force.

A Run In With Jackson…Ms. Jackson

On June 18th, the men of the Fourth would themselves passed through Alexandria, VA. While there, they marched along King Street and passed the infamous Marshall House, where Colonel Ellsworth had been killed by the inn keeper, James Jackson. In the weeks since his murder, Ellsworth had become a martyr for the cause of Union, and the story was well known to practically everyone in the nation, especially the soldiers stationed around Washington : There had been an extremely large Confederate flag hanging from a pole of the hotel, to the point where some said it was plainly visible from Washington City. Ellsworth and four of his New York Fire Zouaves went up to the roof of the Marshall House to tear it down. The banner was successfully pulled down, but as Colonel Ellsworth descended the stairs, the owner Jackson himself appeared and opened fire with a double barrel shotgun at near point blank range. The Colonel was dead instantly, and Jackson was quickly shot down by Corporal Francis Brownell, one of Ellsworths’ soldiers.

The Marshall House, Alexandria, VA. Site of the death of Ellsworth, and a month later, the site of a dognapping at the hands of the Fourth Pennsylvania, Co. “A.”

It is no surprise then that at some point during this passing that one or several of the men opted to grab a souvenir from the Marshall house. This was a common occurrence and the hotel was practically stripped bare by relic hunters. However, this was one item that the rightful owner would soon come back to collect. Three weeks later, on July 10th, Jacksons’ very own daughter arrived in the camp of the Fourth Pennsylvania looking to speak to Captain Bolton of Co. “A.” According to the diary of Captain Bolton, Ms. Jackson claimed that one of his soldier’s had actually taken James Jackson’s dog right from the Marshall House.

July 10th – “…in the evening,received a visit from the daughter of Jackson of the Marshall House fame, in regard to a dog belonging to the family, said to be harbored in my company.”

Unfortunately, Captain Bolton’s journal does not mention the outcome of the meeting, but it could be safe to assume that the canine souvenir was returned to it’s rightful owner.

“Kill The Farmer.”

On June 24th, the regiment was ordered to Shuter’s Hill, just outside of Alexandria, in anticipation of movement by the enemy on the Federal Capitol. Regular drill and inspections occurred here, and the regiment honed it’s field prowess.

On the night of June 30th, pickets under the command of Lt. Matthew McClennan were posted along the old Fairfax Road. At about 2 a.m., they were attacked by approximately thirty Confederates, and here the regiment would accrue another casualty. 23 year old Norristown farmer Thomas Murray of Co. “E” was killed, while Charles H. Rumer, also of Co. “E,” was wounded. A third picket narrowly avoided injury, and hid from the enemy by laying still on the ground, enveloped in the darkness. Murray’s last words as he lay dying were, strangely, “Kill the farmer.”

As an interesting side note, a Confederate Sergeant by the name of Haines was also killed in the melee. He had formerly been a clerk in Washington city before the war; after the fight, his body was picked up and brought into camp on a cart for the rest of the men to view. Some of the men had yet to see a “real rebel.”

A Request from the Commanding General

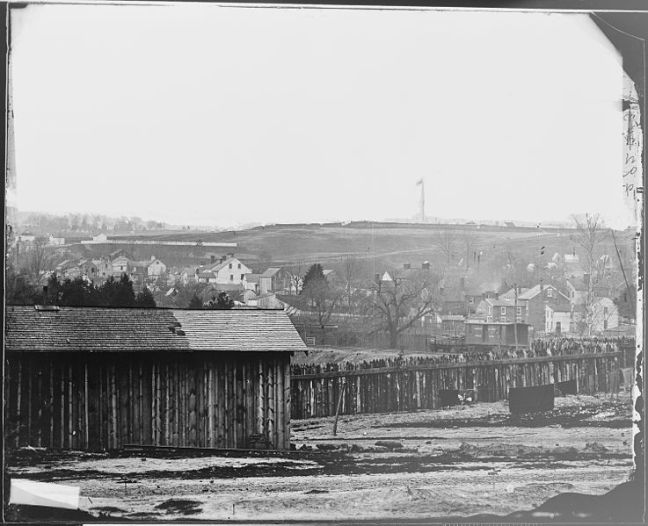

Centreville, VA. The Fourth Pennsylvania was camped in this vicinity when the request to remain for 2 more weeks came from General McDowell on July 20, 1861.

By July 18th, the men of the Montgomery Regiment were sick, tired, hungry, ill equipped, and ready to go home; their enlistments were set to run out in two days. July 19th dawned with no change; there was still little food, no rest, and no movement. July 20th started with the same circumstances, however this was the day that the enlistments ran out, and the men could finally look forward to returning home. This feeling of relief was broken when General Irvin McDowell himself delivered a message to Colonel Hartranft and his men :

Special Order No. 37

Headquarters, Dept. Northeastern Va.

Centreville, July 20, 1861.

The general commanding has learned with regret that the term of service of the Fourth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers is about to expire. The services of this regiment have been so important, its good conduct so general, its patience under privations so constant, its state of officering so good, that the departure of the regiment at this time can only be considered an important loss to the Army.

Fully recognizing the right of the regiment to its discharge and payment at the time agreed upon when it was mustered into the service, and determined to carry out literally the agreement of the Government in this respect, the general commanding nevertheless requests the regiment to continue in service for a few days longer, pledgeing himself that the postponement of the date of muster out of service shall not exceed two weeks. Such members of the regiment as do not accede to this request will be placed under the command of proper officers to marched to the rear, mustered out of service, and paid as soon as possible after the expiration of their term of service.

By command of Genl. McDowell;

James B. Fry,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

Captain William Bolton, Co. “A,” can best explain what happened next. :

“July 20 – …the term of enlistment of the regiment expired to-day. General McDowell made an appeal in a Special Order, asking the regiment to remain a few days longer, and pledgeing that the time of muster-out of service should not exceed two (2) weeks. Difference of opinion prevailed through-out the whole regiment, but there was no concert of action. Many were willing to remain, I among the number.

The fact of the matter was, the men had been badly used. They had a right to their dis-charge. Many had already made provisions to reenlist in the service after a short stay at home. I myself had a part of a company already enlisted for the new call of three years men. The General, seeing that nothing could be done, in Special Orders, ordered the regiment to retire to their old camp to report to General Runyon to be mustered-out.”

General Irvin McDowell

There was heated discussion amongst the regiment, as to what to do next. Some men elected to stay and serve, per the General’s request; other men wanted no part; they had served their required time and wanted to go home. As Captain Bolton had mentioned, many men had already planned their next move in the service, and would be returning to the ranks in new 3 years regiments shortly after their return home. No one in the ranks of the regiment was aware that battle was imminent, and the officers above them intimated very little to that fact. The men who elected to leave did not know that the next day would bring the first great battle of the war. They expected that if they stayed, it would be another two weeks of drill and picket duty, mixed with plenty of boredom and discomfort, and they would have no more of it. Regardless, as a consensus could not be reached by the men, the commanding General decided it would not be best to take only part of the regiment into battle if one should come.

General McDowell himself issued the order for the official discharge of the Fourth Pennsylvania, noting that their own Colonel Hartranft himself volunteered to remain with the army :

Special Orders No. 39

Hdqtrs. Dept. N.E. Va.

Centreville July 20, 1861.

I. The Fourth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, having completed the period of its enlistment, is hereby honorably discharged from the service of the United States. The regiment will, under the command of the Lieutenant Colonel, take up the march tomorrow for Alexandria, and on its arrival at that place will report to General Runyon to be mustered out of service.

II. Colonel Hartrant, Fourth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, having volunteered his services, is assigned to duty on the staff of Colonel Franklin, commanding brigade.

x x x x

By order of General McDowell:

James B. Fry

Assistant Adjutant-General.

To The Rear

As mentioned in the official discharge order given, Colonel Hartranft decided to remain behind with the army, and was assigned to the General Franklin as an aide-de-camp. Not mentioned in McDowell’s official document is that Captain Walter H. Cook of Co. “K” also remained behind, and was in Hunter’s division as a volunteer aide-de-camp also. Meanwhile, the rest of the Fourth PVI marched out of camp early on the morning July 21st, under the command of Lt. Col. Schall, and marched 24 miles back to Alexandria.

The battle of Manassas began after they had left the area, and the regiment was nearly to Alexandria as the battle picked up. There, late in the day, they encountered the fleeing Federal army, and the men of the Fourth manned the defenses of Alexandria to cover the retreating masses during “the Great Skedaddle.”

Major Schall would write after that battle, “…They resolved to remain to support the garrison at Fort Ellsworth and to assist the retreating army.” As the rest of the federals retreated in disarray, the Fourth Pennsylvania remained steadfast, and manned the works in anticipation of a Confederate move on Washington that was surely anticipated after their victory.

Fort Ellsworth is shown in the distance of this photo, on top of Shuter’s Hill overlooking Alexandria, VA. This shows the fort later in the war; at the time of First Manassas when the 4th manned these works, it was still very much under construction and did not have this more finished appearance.

Heading Home

The Fourth broke camp and moved to Washington on July 23rd. From there, they moved to Baltimore, and by 8 pm on the evening of the 24th, they were once again on Pennsylvania soil, bivouacked on the grounds of the state capitol. They remained there for several days until muster rolls and discharges were issued; however, by Friday the 26th the word of the supposed cowardice of the Montgomery Regiment had reached Harrisburg, and a “melee” ensued between men of the Fourth and men of the Second Pennsylvania. Both regiments were waiting for their final muster-out and pay, when, during the argument, 19 year old Sergeant George Starry, Co. “I,” Second PVI, pulled a pistol and shot 20 year old Pvt. George A. Reiff of Co. “B.” as well as Pvt. James Ashton. Ashton would survive, but Reiff would die of his wounds on the 29th of July, the final casualty of the Fourth Pennsylvania’s brief career. Starry was tried for the murder in Harrisburg, but would be acquitted. He would serve in the Seventh Pennsylvania Cavalry and rise to the rank of Lieutenant; he would live into the 1930’s.

The rest of the men of the Fourth reached Norristown on July 28th, arriving at approximately 3 a.m., where a street parade was held, and they initially received a “hearty welcome” by the majority of the people of their home city. Major Schall would note in a letter in his newspaper the Independent, “We confess we felt grieved when we heard, on our return, that some of our own citizens had stigmatized us as cowards and heaped all sorts of abuse upon us because, when our term of enlistment had expired, we dared to return to our homes.”

McDowell’s Scape Goats

On August 4th, Irvin McDowell wrote his official after action report on the battle that had taken place near Manassas, VA. In an excuse laden report, McDowell blames lack of food, road weary “green” soldiers, and general confusion and disorder for the disastrous defeat that would become known as the Battle of First Bull Run. He also blames the fact that many of his soldiers were 90 day enlistees, and that many of them were leaving in droves; however, he particularly names 2 regiments by name, the Forth Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and the Eighth New York Militia Artillery battery.

“On the eve of the battle the Fourth Pennsylvania Regiment of Volunteers and the battery of Volunteer Artillery of the Eighth New York Militia, whose term of service expired, insisted on their discharge. I wrote to the regiment as pressing a request as I could pen, and the honorable Secretary of War, who was at the time on the ground, tried to induce the battery to remain at least five days, but in vain. They insisted on their discharge that night. It was granted; and the next morning, when the Army moved forward into battle, these troops moved to the rear to the sound of the enemy’s cannon.”

A Tale of Two Sisters, and Redemption

Almost immediately following their return home, many of the officers and men of the Fourth prepared to re-enlist in new organizations, this time for a term of three years. By September of that year, a new regiment would leave Norristown under the command of Colonel Hartranft, Captain Bolton, and many other of the officers and men of the Fourth. The designation would be the Fifty-First Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and these men would leave Norristown carrying that same standard that the Fourth left with earlier that year; it would later become known as the Fifty-First’ “First National” and now resides in the flag conservatory at Harrisburg.

Ten months later, several more companies were raised, primarily out of Montgomery County, by raised by veterans of the Fourth. Lt. Matthew McClennan and orderly sergeant George Guss, of Co. “A,” were now Captain’s of two of these new companies. They would arrive at Harrisburg, and be joined with several other companies and be designated as the One Hundred and Thirty-Eighth Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. McClennan would eventually become Colonel of the regiment.

These two regiments, born out of the ashes and unwarranted disgrace of the Fourth Pennsylvania, considered themselves “sister units.” They would go on to earn “unfading laurels” in many of the most brutal engagements of the American Civil War. The Fifty-First would gain everlasting fame as one of the two “Fifty First” regiments that finally took Burnside’s bridge at Antietam in 1862; the One Hundred and Thirty-Eighth was one of the Sixth corps units that helped delay Jubal Early and save the federal capitol at the battle of Monocacy in the summer of 1864.

There is a story in the regimental history of the One Hundred and Thirty-Eighth Pennsylvania that illustrates the sisterhood of these two regiments; during the Overland Campaign, May 5, 1864 :

“…our division being temporarily in reserve, there were many irregular halts, and during one of these – while lying along the Gordonsville Plank Road – the old 9th Corps (having crossed the river in the morning and re-joined the Army of the Potomac) came up and passed us. Glorious Burnside and noble Hartranft were lustily cheered. Old friends – of the 51st and 138th regiments – warmly greeted each other, and then separated to share with their commands – in different positions – the perils of the conflict already raging.”

Colonel Hartranft would eventually receive the medal of honor for remaining on the field of Manassas that day, but the disgrace of his men leaving the field would follow him for the rest of his career. He felt that he was denied promotion and position time and time again due to the disgrace of the Fourth. Even Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton knew of this event, and often remarked when Hartranft came before him, “Why, this is the Colonel of the Fourth Penna. Regiment, that refused to go into service at Bull Run?” Hartranft never publicly came to the defense of those men, despite that many would go on to serve alongside him, and in other regiments.

Though they did not face the shrieking shells and piercing bullets of a full scale battle like so many others, there can be no doubt that the men of the Fourth Pennsylvania performed their duties and stood tall in the face of the adversity of soldiering. They were some of the first to answer their country’s call, and served their full term of service to the end despite mistreatment and lack of proper uniforms and equipment. It was only by pure happenstance that the first great battle of the war took place the day after their term of enlistment ended, and even then, when the sound of the cannons was heard, they did not just “move to the rear” as was said about them. In fact, they once again rose to the occasion and protected the fleeing mass of Federal soldiers streaming towards Washington.

There is no need for a scape goat when it comes to the battle of First Bull Run; the conscience of the descendants of the men of the Fourth should be clear. These men not only fulfilled their assigned duties as the Fourth, but also in the years to come as members of other regiments on many battlefields across the country. These men deserve just as much honor and respect as any other that served. The only person that General Irvin McDowell should look to to blame for the disastrous defeat at Manassas, was in the mirror.

Sources

Bates, Samuel P. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65, Harrisburg, 1868-1871.

Bolton, William. The Civil War Journal of Colonel Bolton, 51st Pennsylvania, April 20, 1861 – August 2, 1865. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania. Combined Publishing, 2000.

Dixon, Mark E. “The Truth of the First Battle of Bull Run.” The Truth of the First Battle of Bull Run. Main Line Today, n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2016.

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of he Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources. Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908.

Gambone, A. M. “General and Governor; John Frederick Hartranft.” The Bugle : The Quarterly Journal of the Camp Curtin Historical Society and Civil War Round Table, Inc. 15.3 (2005): n. pag. Web. 22 Dec. 2016.

Gambone, A. M. Major-General John Frederick Hartranft: Citizen Soldier and Pennsylvania Statesman. Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 1995. Print.

Lewis, Osceola. History of the One Hundred and Thirty-Eighth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Norristown, Pennsylvania. Wills, Iredell & Jenkins, 1866.

McDowell, Irvin. Report of Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, August 4, 1861. “Official Records of the Civil War – Battle Reports.” Official Records of the Civil War – Battle Reports. Web. 07 Dec. 2016.

Parker, Thomas H. History of the 5lst Regiment of P.V. and V.V. From, Its Organization at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Pa., in l86l, and Its Being Mustered Out of the United States Service at Alexandria, Va., July 27th, l865. Baltimore, MD: Butternut & Blue, 1998 reprint of 1869 ed.